Background (Agribusiness)

Sector Background and Potential

The Philippine agricultural sector comprised 19% of GDP in 2009 and employed 34% of the labor force. Yet agricultural products made up only 8.3% of total Philippine commodity exports and Philippine agricultural exports were the smallest of the ASEAN-5. Table 22 contains agricultural exports and imports of the ASEAN-6 (less Singapore) for 2009 and shows that the Philippines exported US$3.2 billion, a very small amount compared to Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam.<sup “>34 Of the five economies, only the Philippines imported more agricultural goods than it exported. Agricultural exports for the other four economies made significant, positive contributions to their trade balances.

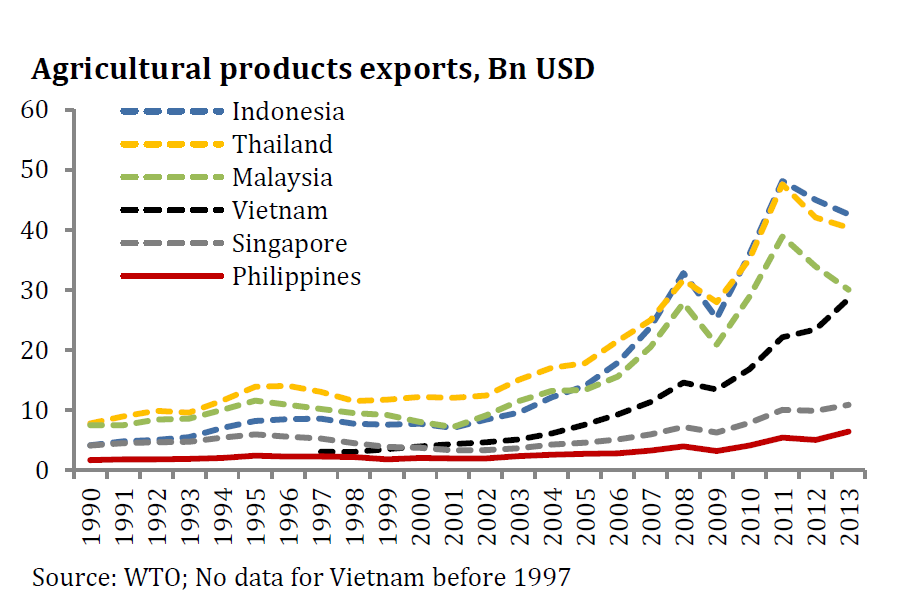

Figures 58 and 59 show agricultural exports of the same countries from 1990-2009. By comparison, Philippine agricultural exports declined from comprising about the same 20% share in 1970 of ASEAN-6 total agricultural exports as Thailand and Indonesia – while Malaysia held a larger 30% share – to being the lowest among the ASEAN-6 in 2009, around 3% of the ASEAN-6 total. During these nearly two decades (1990-2009) total ASEAN-6 agricultural exports grew strongly, increasing about 20-fold, while the Philippines fell behind Vietnam and Singapore.<sup “>36

About 12 million Filipinos work in the agricultural sector. If the country can significantly increase its exports and imports of agricultural goods, agricultural provinces would generate much greater revenue, provide more employment opportunities, and lessen poverty in rural areas. This is especially important for Mindanao, the country’s breadbasket that has great underdeveloped potential for agricultural exports.

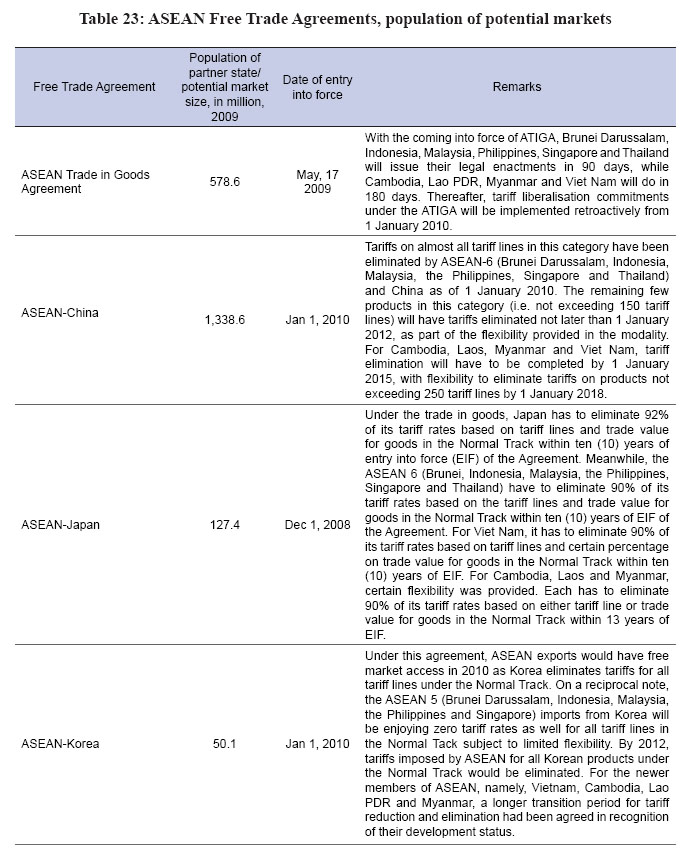

New free trade agreements coming into effect in ASEAN present both challenges and opportunities to the agricultural sector. The ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) will be fully implemented in 2010, others in subsequent years (see Table 23).

The total estimated population of these FTA economies is more than 3.3 billion (including the Philippines), giving Philippine exporters unprecedented access to extremely large markets, while also increasing the exposure of domestic markets to imported products from the FTA economies. On the one hand, the Philippines has the potential to provide large quantities of specialized food products to hundreds of millions of consumers with rising incomes. On the other hand, the survival of domestic producers will be jeopardized by inexpensive imported products.

Philippine agriculture needs to fully explore the multitude of new market opportunities these FTAs present. The Philippine Government has the means to inform the agricultural sector of the best new export opportunities, while also developing – in consultation with the private sector – strategies to deal with potential threats to domestic production. For example, what should be done when an influx of lower cost processed poultry and pork arrives from neighboring countries such as Thailand? Are there models for local farmers to enable them to continue their present businesses of raising chicken and pigs?

Competitiveness also requires a level playing field for Philippine exporters. By contrast with the EU – where there are constant efforts to level the playing field among member countries – the ASEAN region lacks appropriate policies and rules.

Filipino farmers are capable farmers. However, they face high domestic transport, labor, and other production costs (see Part 4 Business Costs). The cost of Philippine labor is many times Cambodia’s.<sup “>37 Insecticide costs twice as much in the Philippines as elsewhere in the region.

Because the country is archipelagic, domestic transportation costs are high. Bureaucratic “overkill” is also a problem. Why does a new ethanol plant need Department of Agriculture (DA), Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR), Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), and other government personnel to often “inspect” it? Aggressive steps by both the public and private sectors are needed to solve these problems.

Some local Philippine poultry integrators and commercial hog raisers have the potential to export to new FTA markets. The Philippines enjoys an advantage because some parts of the country are free from Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), and the whole country may be declared FMD-free in the future. The Philippines has also been free of Avian Influenza. Although production costs for hogs and poultry are relatively higher in the Philippines, the most efficient local commercial farms are able to reduce costs significantly and can be competitive.

Backyard farms, which raise only a few animals, face a more serious challenge under the new FTA trading regime. They are less efficient yet comprise 60% of the subsector according to industry experts. Their small scale deprives them of efficiencies needed for competitive export production and marketing.

Although once ahead, the Philippines is now many years behind Thailand in integrating small farms into larger agribusiness enterprises. Nevertheless, the Philippines has successfully demonstrated that large agribusiness ventures that harness many small farmers are possible. SMC proved this form of partnership with its Cassava Assembler Program. Over 4-5 years, 30,000 hectares were put into production by small farmers, 80% in Mindanao and the rest in Luzon and the Visayas. SMC guarantees a floor price, facilitates bank financing for the growers, services the loans from cassava crops, and provides technical and some administrative support. In this model, the cassava may be used for ethanol for domestic fuel blending.

Thailand’s leading agribusiness firm Charoen Pokphand Foods (CP) has started operations in the Visayas and is another example of how the model of integration with small farmers can succeed in this country. CP integrates small farmers within its corporate system. All farm infrastructure is in the hands of the farmers. CP owns the supply of hogs the farmers grow. Farmers are partners. This model has made Thailand an agricultural powerhouse. The integration is deep and extensive, and includes farmers sitting on corporate boards.

Another local example of integration is the business relationship of Nestle with 30,000 small Filipino coffee growers. A non-automotive division of Toyota Tsusho Corporation, which deals in energy and food products, is reportedly discussing with Dole the sourcing of biodiesel from jatropha plants to be grown on at least 200,000 hectares in southern Mindanao for export to Asian and European markets. Jatropha was chosen because it requires minimal water and does not compete with edible crops.

There is an interesting model in Mindanao in the middle of a conflict area. This model reverses the usual pattern of achieving peace before development is possible. Agribusiness firms Unifrutti and La Frutera brought development and peace to several municipalities of Sultan Kudarat and Maguindanao. They found local champions in the late Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) leaders Hashim Salamat and Datu Paglas who wanted to see investment and job creation for their communities. Undeveloped lands were planted to export bananas and several thousand jobs were created and the project has prospered for over a decade. There are large tracts of agricultural lands in southern Bukidnon province and in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) where similar partnership projects could be initiated.

Another best practice model that can be followed for coffee exports is to partner companies with indigenous communities in the Mindanao highlands, where coffee growing conditions are ideal. Buyers provide free seedlings, training, and a conditional cash transfer connected to growing the crop. After the seedlings mature, they buy beans at a premium “fair trade” price and sell to the export market. Coffee production helps protect mossy forestlands and watersheds important for local irrigation. The end consumer of the coffee is willing to pay a premium to help save forests and support poor farmers. This model may apply to other upland crops.

Another export opportunity for small Philippine farmers is natural organic farming. Middle-income families will pay a premium for products such as free-range chicken or natural-grown tomatoes. Natural organic farming is well suited for small farmers who can partner with larger businesses to market their products. Filipinos can be competitive in such products for export to Japan, the US, and other large markets. Small farmers can work together in cooperatives and associations.

Oil palm trees and rubber trees are additional crops that large integrators can work with small farmers to grow, process, and export. However, security is a problem for farms in some areas ideal for growing these crops.

In recent years, interest from the Middle East and Korea in investing in food production in the Philippines has been growing. China, the Middle East, and Japan present promising new market opportunities.

Mindanao has the potential to feed Luzon and to export food. It is typhoon-free with excellent soil and weather. But moving produce from Mindanao to markets in other parts of the Philippines remains expensive. According to industry sources, shipping a container of corn from Taiwan to Manila costs US$ 100-200 on average, but from Mindanao to Manila the cost, as high as US$ 1,000-2,000, deters development. With lower transport costs, vegetables from Bukidnon could feed Metro Manila. In Cambodia, the World Bank conducted a thorough study of steps in the agricultural supply chain in order to suggest actions to reduce costs.

There are other long-standing farm infrastructure requirements needing continuing new investment: farm-to-market roads, post-harvest processing facilities, irrigation, phytosanitary inspection facilities, food terminals, cold storage, and food processing factories to allow more local value-added and to take advantage of the new international container port at the Phividec Industrial Estate in Northern Mindanao.<sup “>38

There has been too little investment in irrigation since 1994. Tube wells are more efficient for irrigation than gravity. A tube well involves boring a 5-8″ wide stainless steel pipe into an underground reservoir. An electric pump at the top (or small wind mill) lifts water for irrigation.

Despite the long-standing example of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Baños, the Philippines spends a tiny amount on research and development (R&D), only about 0.12% of GDP.39 There are only three seed companies in the country. Taiwan and Thailand each have dozens of seed companies working on their local R&D. The UP Los Baños agricultural school produces excellent technical articles, but there is a long gap between writing papers and their application in production. There is also a gap between what is actually happening on farms and publishing research studies in journals. Information about best practices being followed in different regions, for example Region 11 in the banana and abaca industries, could be forwarded to other provinces in Mindanao.

The Philippines has little formal central planning seeking to create economies of scale for competitive agricultural export products such as the current leaders: coconut, fish, seaweed, sugar, and tropical fruits (e.g. bananas, mangoes, papaya, and pineapple).

Zoning should be done with the private sector, the people who use the land. Suitable crops should be chosen for the right areas. Products that are most likely to be exported should be prioritized. For example, the Region 11 Regional Development Council (RDC) has a good mixture of public and private sector representatives for planning and zoning in the region. It is composed of governors, regional directors, and the private sector. Businesses, NGOs, and the educational sector are represented and able to influence planning for agriculture.

Countries that are successful in agriculture are ones that have good land settlement and land reform policies, security of land tenure, and small farmers able to sell their land to larger farms. Currently this is not allowed in the Philippines given the 5-hectare ownership limit. In other countries that have instituted land reform, after the distribution of land to farmer beneficiaries has been completed and new owners have security of title, they are allowed to mortgage or sell their land. As long as the small farmer is given a title, how he uses it – to farm, rent, or sell to someone else – should be up to him. The recent 5-year extension of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) will give the program a total life of 25 years, a quarter-century. Agrarian reform in the Philippines should end when this law expires after five more years to complete the task. Then limits on landholding should be lifted.

The Agri-Agra Law should be modified. Because mandatory lending does not work, there are few benefits for the agricultural sector. Most banks pay a small penalty not to lend.

CARP beneficiaries cannot sell nor mortgage their land for 10 years, and thus cannot capitalize on their property. Laws should be passed to allow them to do both.

The DA has been engaged for the last two years in preparing an inventory of agricultural lands that can be used for large agricultural export ventures.

The Philippine Agribusiness Development and Commercial Corporation (PADC) has set up a Philippine Agribusiness Center at the DA (www.philagribiz.com) which works with Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR), DENR, Board of Investments (BOI), Philippine Economic Zone Authority (PEZA), and others to develop two million hectares, a goal of the Medium Term Philippine Development Plan (MTPDP) include working with investors in biofuels, biomass, and other high value crops.

Financing is always a critical issue for agribusiness. Both Landbank and Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) have underutilized financing programs for agriculture, yet the Agri-Agra law was recently amended to increase mandatory bank lending to agriculture from 10 to 25%. In the past, banks have not met the 10% level and will probably not meet the higher 25% level, and will instead pay the small penalty. The DA is in discussion with International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) to develop a special fund that can tap OFW remittances (US$ 17 billion in 2009) to invest in agribusiness projects.

A study discussed by an FGD participant has recommended establishing an Agribusiness Investment Fund with a capitalization of PhP 50 billion. Majority (51%) of the funding should be private while the rest should come from the government, e.g. the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) and Social Security System (SSS). It should be 60% Filipino-owned so there would be no issues over land ownership. At least 70% of the fund should be reserved for investment in agriculture, infrastructure, and education in Mindanao, while the other 30% could be reserved for other agribusiness regions in the country. Investment bankers familiar with Mindanao should manage the fund. At an average of PhP 100,000 to create one job, this PhP 50 billion could create 500,000 jobs. Grants or soft loans to the fund can be included as preferred stock redeemable over a long period of time, thus improving returns to the common stock and diversifying risk. The Agri-Agra law could be modified to make the fund an eligible investment for financial institutions. The fund can be an alternative investment for banks instead of lending money to farmers.

Agriculture has become less attractive to young Filipinos and to entrepreneurs. There is a shortage of farm managers with adequate entrepreneurial skills. Few college students major in agribusiness. Yet education remains a great enabler for increased agribusiness activity. Agricultural education programs in Mindanao should be improved to meet the urgent need for future agribusiness managers. Entrepreneurship should be a core subject in training programs.

France, Switzerland, and Germany have models for training programs that may apply to the Philippines. France has family farm schools, Germany has dual training centers, and Switzerland has agricultural entrepreneurship training. Short training courses should be available to farmers and students in high school. Foundations and educational/research institutions such as the MFI Farm Business Institute can develop, organize, and fund entrepreneurial and management training. Rice and corn development and proponents of genetically modified crops should expand their current agricultural education programs with high schools and universities in Mindanao.

The failure of agricultural cooperatives in the Philippines is due to mismanagement. Farmers have no formal entrepreneurial and managerial training. Fund management is usually a serious problem; senior managers in cooperatives are often paid unjustified high salaries. The government should assign a competent manager for every area of land given to farmers under the CARP. The Philippines can learn from the success of South Korean agriculture cooperatives.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) are providing technical and training assistance. In Region XI JICA has supported eight cluster groups with funds to replant 50 hectares of barren land with falcata trees, intercropped with coffee, creating 150 jobs, reforestation, a means of livelihood, and carbon credits.

The Korean and Philippine governments have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) for the Multiple Industry Cluster (MIC) project that includes agribusiness. The Philippines will identify 100,000 hectares to be made available, and South Korea will invite investors to locate in the MICs. KOICA will provide technical assitance. Both governments will provide the data framework for possible Korean investors. A KOICA rural development project has completed a rice mill in the Aurora province; the rice is being sold as KOICA rice. KOICA has also put up a US$ 4 milllion job training center teaching farmers how to plant and harvest larger crops.

Footnotes

- The category is broader than the agricultural goods exports released by NSO (US$ 2.2 billion). This includes SITC sections 0, 1, 2, 4 minus 27 and 28 (WTO definition).[Top]

- Ibid[Top]

- Sources: FAO and WTO[Top]

- Cambodia is becoming a producer and potential exporter of ethanol, as is the Philippines.[Top]

- Only 14% of local roads in the Philippines are paved. Local roads comprise 85% of the total road network in the country.[Top]

- Latest data is 2005, World Development Indicators 2010, World Bank[Top]