U.S. Reaches Trans-Pacific Partnership Trade Deal With 11 Pacific Nations

October 6, 2015 at 14:30

U.S. Reaches Trans-Pacific Partnership Trade Deal With 11 Pacific Nations

By The Wall Street Journal | By WILLIAM MAULDIN | Updated Oct. 5, 2015 9:53 a.m. ET

Trans-Pacific Partnership created after bitter fights over automobile industry, intellectual property rights and dairy products

Among other things under the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Canada and Japan agreed to increase access to their tightly controlled dairy markets, allowing in some American dairy products. PHOTO: MIKE GROLL/ASSOCIATED PRESS

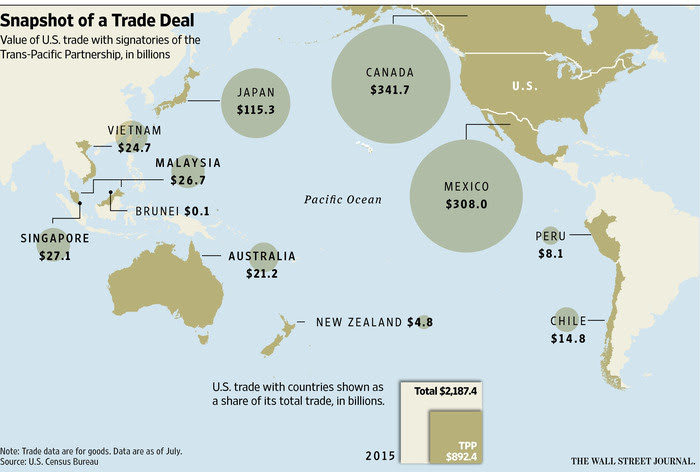

ATLANTA—The U.S., Japan and 10 countries around the Pacific reached a historic accord Monday to lower trade barriers to goods and services and set commercial rules of the road for two-fifths of the global economy.

For the U.S., the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement opens agricultural markets in Japan and Canada, tightens intellectual property rules to benefit drug and technology companies, and establishes a tightknit economic bloc to challenge China’s influence in the region.

The deal is a victory for President Barack Obama, who sees it as boosting economic growth, enhancing competitive industries and binding like-minded Pacific countries at a time when China—not a part of the bloc—is adopting a more assertive economic and military posture in the region.

But Mr. Obama faces a steep challenge in the months ahead to win approval for the deal in a deeply divided Congress. Only a handful of Democrats support Mr. Obama’s trade policy, and Republican support is unpredictable in the 2016 election year, depending on the stance of presidential candidates and new leadership in the House. As it is, the deal can’t go to a vote before Congress until early next year.

After dozens of rounds of negotiations and five days of haggling in Atlanta, trade ministers and other top officials said they resolved bitter fights over intellectual property protection for biologic drugs, automotive-assembly rules and dairy products.

The deal, if approved by Congress, will mark an effective expansion of the North American Free Trade Agreement launched two decades ago to include Japan, Australia, Chile, Peru and several southeast Asian nations.

The trade deal has been in the works since 2008 but has been stymied by politically sensitive disputes, including a fight between the U.S. and Japan over the automobile industry.

One of the last disputes to be resolved pitted Australia against the U.S., which was seeking up to 12 years of protection for biologic drugs against generic imitators. The two countries reached a complicated compromise that provides at least five and potentially up to eight years of exclusivity for biologics. Chile, Peru and other countries remained concerned about adding to the price of drugs through long exclusivity periods, according to people following the talks.

In another last-minute deal, Canada and Japan agreed to increase access to their tightly controlled dairy markets, allowing some American dairy products in, but New Zealand also persuaded the U.S. to accept more of its milk products. The sour milk fight caught the attention of Congress, where Sen. Ron Wyden (D., Ore.) and Rep.Paul Ryan (R., Wis.), two lawmakers overseeing trade policy, demanded that dairy producers in their states gain more access to Canadian consumers, a sensitive concession for Canada during its own election season.

The Pacific agreement is expected to face a tough battle in Congress that could carry on to the next administration. Mr. Obama will have to allay unease over the deal within both parties in the midst of a heated presidential campaign.

Legislation designed to expedite passage of the agreement through Congress passed narrowly last summer, and a variety of factors, including the pressures of the presidential campaign, could make the final deal a harder sell. Lawmakers from both parties have expressed reservations over provisions in the deal in recent days, including a number who voted in favor of earlier legislation to move ahead on the pact.

The odds of passage in Congress will hinge in large part on the final language in a number of provisions, ranging from the strengthening of rights for labor unions to whether U.S. cigarette companies will face special limitations within TPP countries.

“I will carefully scrutinize it to see whether my concerns about rushing into a deal before meeting all U.S. objectives are justified,” Sen. Orrin Hatch (R., Utah), chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, said in a statementSunday before the deal was completed.

Mr. Hatch has long backed 12 years of exclusivity for biologic drugs, and congressional staffers attending the talks Sunday said they were still digesting what the U.S.-Australia compromise could mean for drug companies. PhRMA, representing some of the biggest U.S. pharmaceutical companies, said it was “disappointed” with the agreement but would evaluate the details.

In pharmaceuticals and other industries, U.S. officials sought a deal that would be acceptable to other countries and as many members of Congress as possible, without triggering the outright opposition of a major business group.

Many Democratic lawmakers and groups backing generic drugs and less expensive medicine didn’t want any more than five years of exclusivity for biologic drugs, and it wasn’t immediately clear if the compromise in the TPP would satisfy their concerns.

U.S. labor unions and their allies among consumer and environmental groups are among the biggest critics of the TPP. The left-wing opposition has prevented Mr. Obama from getting many fellow Democrats—already skeptical of the deal’s benefits to U.S. workers—to support his trade policy.

An array of Republican lawmakers object to provisions that would strengthen the influence of labor groups, impinge on the ability of tobacco companies to fight against packaging rules and other laws overseas, and possibly harm local industries, from dairy farmers tosugar.

With key provisions on the environment and labor rights, Mr. Obama may pick up some Democratic votes in Congress that opposed the “fast track” legislation earlier this year.

The TPP includes stepped-up powers for the U.S. to put pressure on developing nations to improve labor practices — such as requiring Vietnam to allow independent trade unions and Malaysia to cut down on human trafficking.

Under the internationally enforceable framework, the governments in the 12-nation bloc will be able to challenge fellow countries if they don’t follow through with labor-action plans established in the negotiations.

Many U.S. lawmakers have also sought binding rules that would punish trading partners for alleged currency manipulation.

While such currency rules are absent in the TPP, the U.S. and TPP partners are putting the finishing touches on a side deal to the trade agreement in which nations would pledge not to devalue their currencies in such a way as to gain an edge on their competitors, according to a person familiar with the negotiations.

The currency framework, worked out among finance ministries and central banks, won’t have any enforcement provisions, the person said. Instead, representatives of the countries would meet at least once a year to discuss the commitments and to try to coordinate macroeconomic policies.

—Bob Davis contributed to this article.

Source: www.wsj.com