What to do with rusting cars at Cagayan free port?

September 11, 2015 at 13:10

What to do with rusting cars at Cagayan free port?

12:10 AM September 9th, 2015

USED Hyundai Starex vans from South Korea slowly deteriorate as they are exposed to the elements at the car lot of the Cagayan Special Economic Zone and Freeport in Barangay Casambalangan in Santa Ana, Cagayan.

FROM ACROSS the road, car painter Edgardo Villareal, 42, looks at the clusters of abandoned vehicles at the five-hectare car lot inside the Cagayan Special Economic Zone and Freeport (CSEZFP) in Casambalangan village in Santa Ana, Cagayan province. He recalls how he used to earn as much as P1,000 on a good day, more than enough for his and parents’ needs.

All of that changed when in December 2013, the once brisk business stopped.

“It would be a pity if all of these would go to waste. The government should do something so that these vehicles will be sold, so that all will benefit,” says Villareal, who used to do paint jobs on imported cars sold at what locals call “yarda,” or the CSEZFP car lot.

It was the last of four shipments of 1,352 imported vehicles that arrived in Port Irene from Dec. 14, 2013 to Feb. 22, 2014 and were supposed to have been covered by a Supreme Court order banning their importation.

Today, hundreds of Japanese and Korean-made subcompacts, sedans, sport utility vehicles (SUV) and vans sit idly, almost buried by overgrown grasses and slowly getting eaten up by rust and decay. The yard that used to be a busy car trade center and showroom has become a virtual junkyard.

Villareal and 500 local workers—drivers, mechanics, porters, electricians, welders, helpers—who were laid off by the stoppage have learned to move on with their lives and have found jobs elsewhere, says Casambalangan village chair Gavino Ruiz.

“[Those] from other provinces have gone home while those who decided to marry here learned to embrace fishing or farming as their main means of livelihood,” he says.

The used car traders, who lived in the village for years, have also left, leaving behind the imported cars, worth millions of pesos, to the care of maids and security guards.

New hope

But the displaced workers have found new hope of returning to Casambalangan, amid reports that the used car business there would again be revived should the Bureau of Customs (BOC) allow the registration of the more than 900 vehicles remaining in the yard.

Sources said a group of importers has asked Customs Commissioner Alberto Lina to lift the ban issued by his predecessor, John Phillip Sevilla.

“They are asking that these remaining units be registered and sold in order for them to recoup their capital and at the same time allow the government to collect the taxes due, instead of allowing them to be put to waste,” said the source, who asked not to be named for lack of authority.

In a Jan. 7, 2013 decision, the Supreme Court barred Forerunner Multi-Resources Inc., a Cagayan Economic Zone Authority (Ceza)-licensed car importer, from bringing in more vehicles to the country and upheld the constitutionality of Executive Order No. 156 as a “valid police-power measure addressing an ‘urgent national concern.’”

EO 156, issued by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2002, prohibited importation of second-hand vehicles into the country, with a few exceptions.

The SC ruling prompted then Customs Commissioner Ruffy Biazon to order the suspension of processing of the imported vehicles as he sought clarification on the “seemingly conflicting” provisions of EO 156 and EO 148.

EO 148, issued by Arroyo in 2005, declared the legality of used vehicle importations but modified the tariff rates originally imposed on them by the issuance.

It was this law that used car traders, using the license of another importer, Fenix (Ceza) International, continued processing and selling vehicles for the next nine months, arguing that Fenix was not barred by the Supreme Court decision.

However, after Biazon resigned in 2013, his successor, Sevilla, immediately directed its collection office in Aparri town, which covers Port Irene, to strictly implement

EO 156 and stop the processing of vehicles imported through the CSEZFP.

Sevilla’s Dec. 16, 2013 memorandum turned out to be the coup de grace for the used car trade at the CSEZFP.

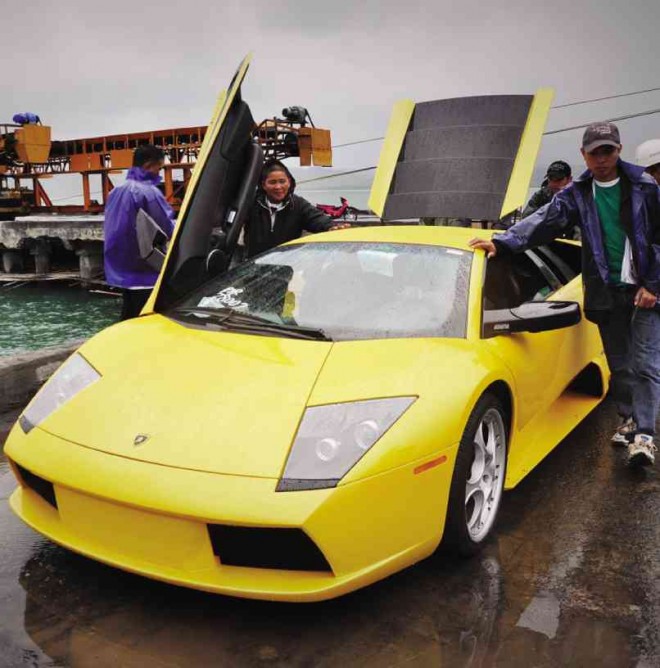

WORKERS help unload a sports car that was part of a shipment of second-hand vehicles that arrived in the Cagayan free port. PHOTOS BY MELVIN GASCON

Windfall

The BOC expects to collect around P150 to P200 million in tariff duties should the Department of Finance allow the agency to accept the import entries for the more than 900 vehicles stuck at CSEZFP.

“That is a win-win solution. We will be able to help locators stem their losses, while it can also help with our collection,” said Arienito Claveria, officer in charge of the Aparri BOC office.

But for the BOC to allow the processing of the remaining imported vehicles would be like walking on a tightrope, he said, given the legal issues that have compounded the industry for years.

For 2015, the Aparri collection office was given a target of P300 million. With three months left in the year, it has collected only P6 million or 98 percent short of its target.

To meet its target, the Aparri collection office has relied heavily on the used car

importation at CSEZFP. In fact, its upgrade from a subport to a district office was

attributed to its potential as a revenue collection arm for the Cagayan free port, says retired District Collector Leilanie Alameda.

In 2012, BOC Aparri earned P312 million, mainly from tariff duties on the used car industry at Port Irene. This amount ballooned to P505.2 million in 2013, this time buoyed by revenues from the importation of equipment for the windmills of Ilocos Norte.

Diminishing chances

But as the government mulls on the proposal to lift the ban, time is not on the car importers’ side, as every day of delay diminishes chances that the vehicles will be revived into running condition after being stuck for more than two years.

Hundreds of vehicles from Japan, which include Honda Fit and Toyota BB subcompacts; Toyota MR2 Spyder convertibles and Nissan Fairlady Z and Mercedes Benz SL200 sedans; Toyota Alphard and Hi-Ace vans; and Toyota Land Cruisers and Mitsubishi Pajeros, will have to undergo conversion from right-hand to left-hand drive.

No such conversion would be required for Hyundai Starex vans and other units from South Korea, but these would have to undergo “major” repairs.

Exposed to sea breeze from the Babuyan Channel, the vehicles’ exteriors have developed stains that may need repainting, while corroded metal parts may have to be replaced.

About 60 “high-end” units are in a better state, sources say, as these are kept inside the enclosed 4,600-square-meter “Philphos” warehouse at Port Irene.

These include Lamborghini, Ferrari, Porsche and Mercedes “supercars” as well as Hummer luxury SUVs, which are kept from public view and under close watch by the Ceza guards.

Other sources, however, say that since the stoppage, a number of these high-end cars have been sneaked out of Port Irene.

“They were hidden inside closed container vans, hauled to the Manila pier via the Cagayan-Ilocos road and shipped to a port somewhere in Mindanao where their registration is processed,” a source said.

In a 2013 interview, car dealers warned that the BOC’s refusal to allow the processing and registration of the imported vehicles would only mean lost revenue, both for the traders and the government.

“The situation here might become another Subic mistake. What happened then? It failed to collect millions [of pesos in import duties] then later on, the vehicles disappeared,” says Peter Geroue, secretary general of the Automotive Rebuilding Industry of Cagayan Valley (Aric-V).

Source: www.newsinfo.inquirer.net