Legislation

The Philippines has been praised among developing countries as having good laws, ones that others have copied. A good example is the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 (RA 7942), considered by international authorities as among the best anywhere. But there also are some laws that have changed little over many decades, such as the Flag Law regarding government procurement, the Public Service Act (CA 146 signed in 1936) concerning public utilities and franchises, and the Philippine Immigration Act of 1940.

There is continual need to update old laws through amendments and periodic omnibus revisions, as well as to legislate for new issues not covered by existing laws. Examples would be the Rationalization of Fiscal Incentives, a comprehensive reform of 92 incentives scattered through many old laws, and information technology bills dealing with issues that hardly existed a decade ago.

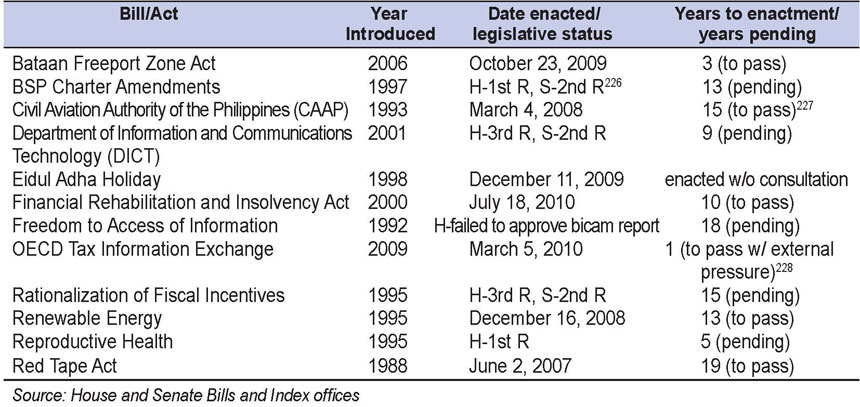

The pace of legislation is usually measured, deliberate, and slow. See Table 70 for examples. A bicameral legislative body is not designed to legislate rapidly. Bills must be passed separately by both House and Senate, their differences reconciled in bicameral committee, and approved in plenary before enactment. Speeding up legislation is cited by proponents of constitutional change as one of the main reasons to return to a unicameral parliament.225

Only in the absence of a legislative body are laws passed quickly. Under martial law (1972- 1980) and the post-EDSA people power revolutionary government (1986-1987) presidential decrees and revolutionary executive orders, respectively, could be drafted, signed, and promulgated much faster than under the post-1987 process. The Filipino people restored a bicameral Congress when they approved the current constitution in a referendum in April 1987.

Occasionally bills can move through the Congress in surprisingly short periods. Sometimes these are bills introduced in successive Congresses over many years without advancing, such as the Civil Aviation Authority Act (RA 9497), neglected for 15 years and enacted only after a foreign government downgraded Philippine pilot training under the old Air Transportation Office (ATO). More recently, after the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in April 2009 put the Philippines on a blacklist of countries uncooperative in providing foreign tax authorities access to bank accounts of their nationals, the Tax Information Exchange Act (RA 10021) was introduced and passed in only a year.

Investment Climate Legislation 2001-2013

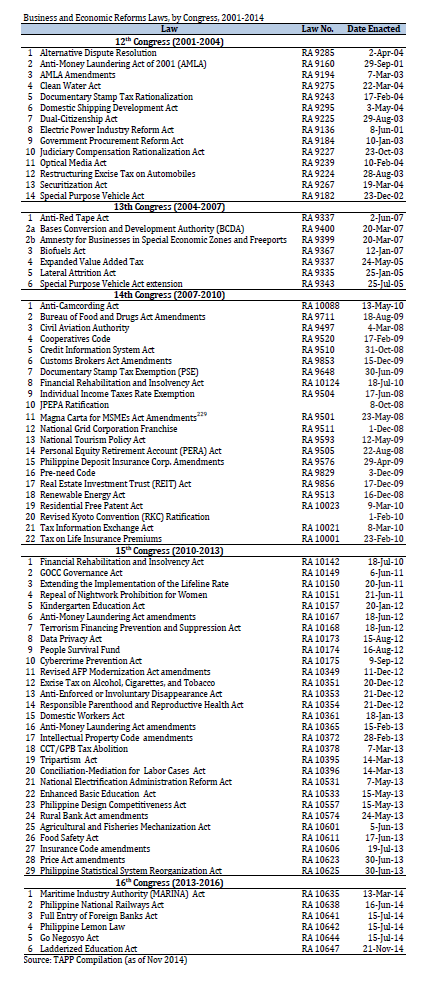

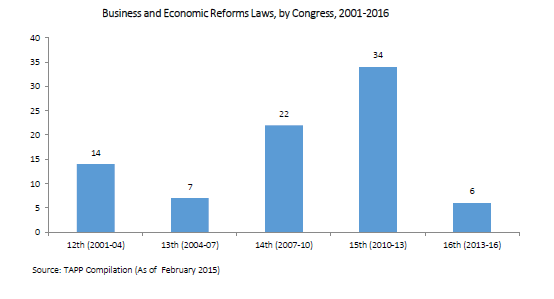

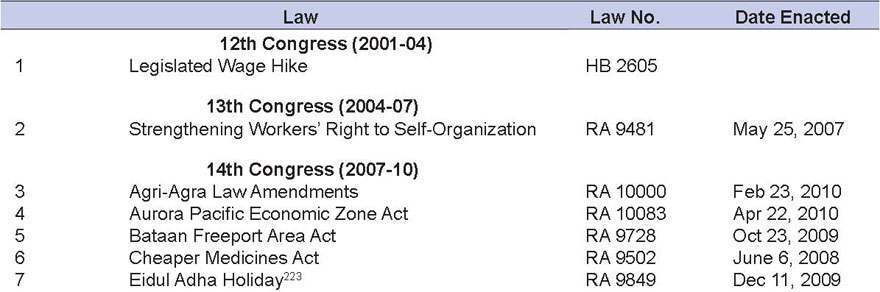

Table 71 identifies significant business and economic reform laws enacted during the last three Congresses from 2001 to 2010. The 12th Congress enacted 14 laws, the 13th Congress 6 laws, and the 14th Congress 22 laws, for a total of 42 new business and economic reform measures. Figure 190 illustrates this data.

Speeding up the pace of enactment of new laws and amending old ones should be a goal of the new Philippine administration. If in the 14th Congress 22 business and economic reform bills were enacted, perhaps this is a good reason to believe that the 15th Congress will pass many more than that number. While this would be a remarkable amount of progressive legislation, it could improve the Philippine economy and its inter-national competitiveness rankings, while inducing investment and creating jobs. With strong leadership and cooperation between the executive and legislative branches, it should be possible to vastly improve the pace of legislation.

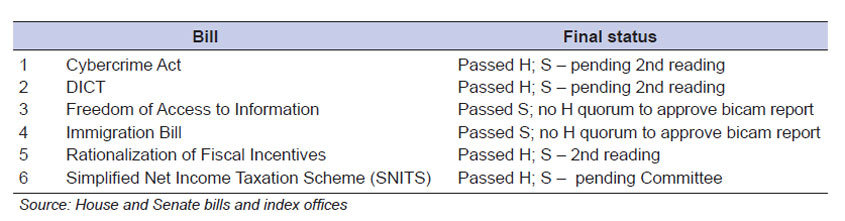

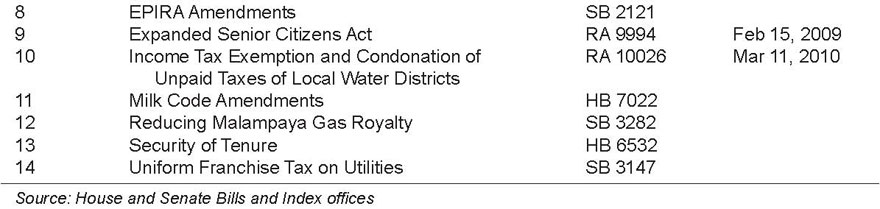

Table 72 lists 6 laws that almost reached enactment in the 14th Congress. Because hearings and floor consideration for most of these were completed in the 14th Congress, it may be possible to enact them early in the 15th Congress. Six Philippine business groups and the seven JFC members wrote President Aquino in July 16 recommending early pass of these six measures.

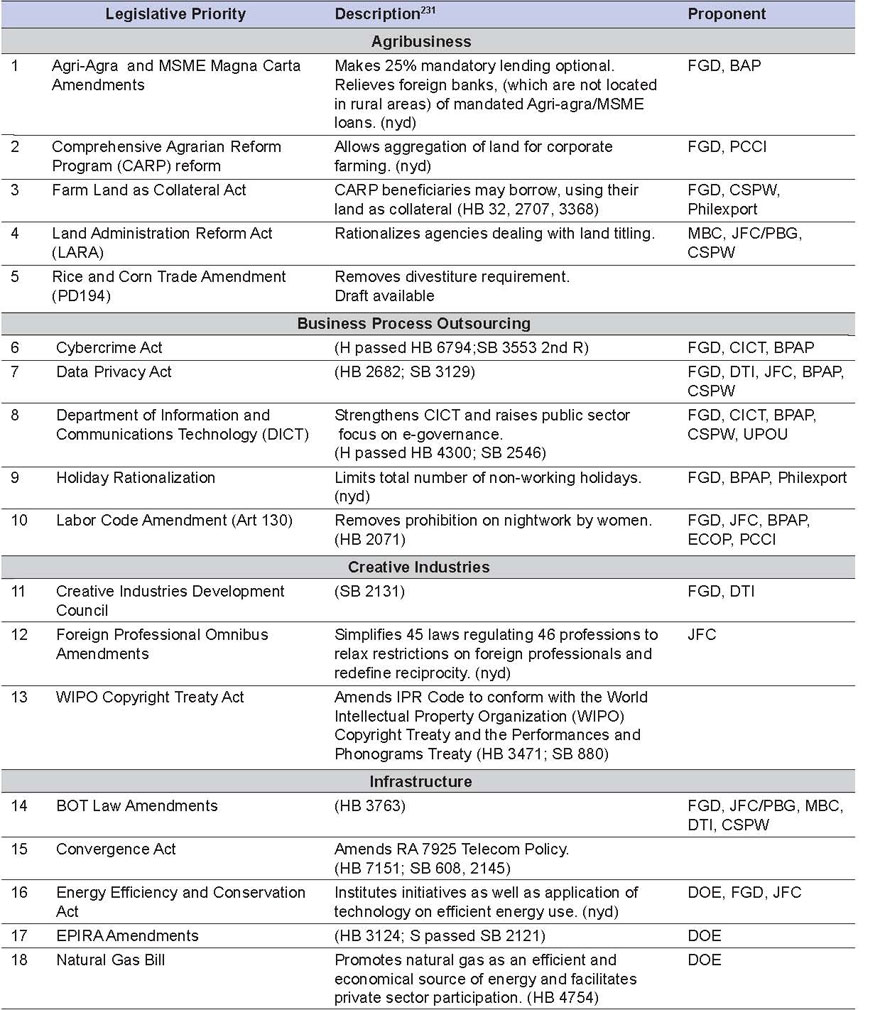

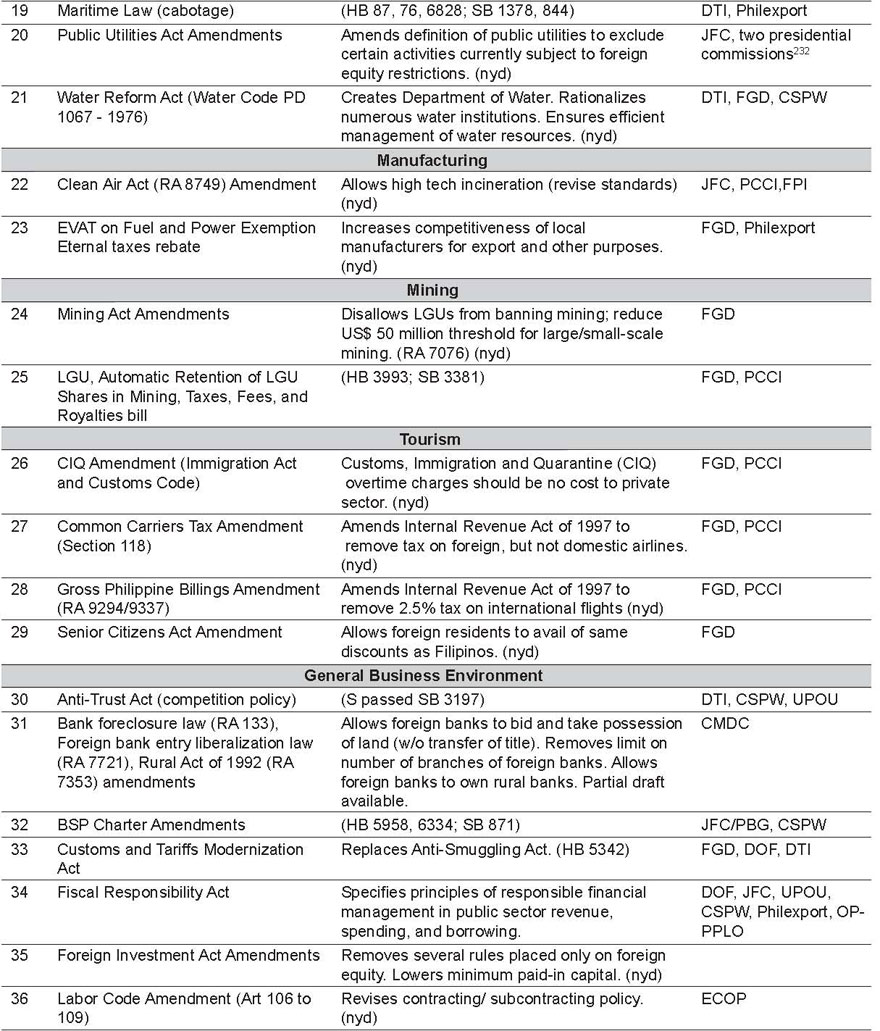

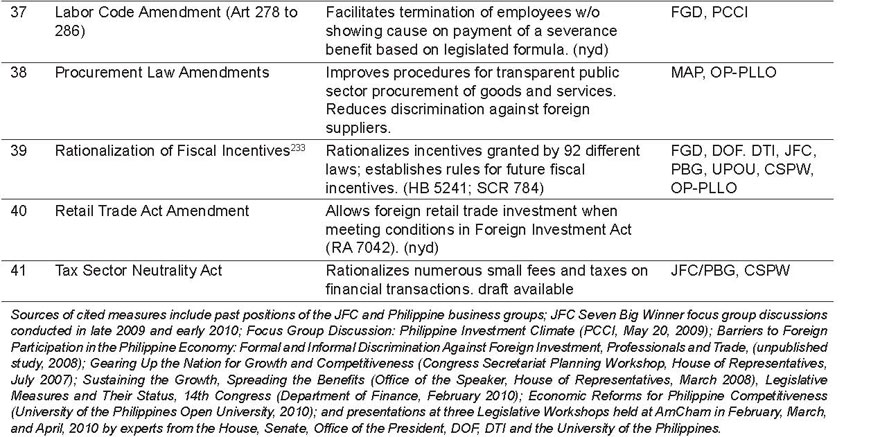

Table 73 is a list of 41 reforms for consideration in the 15th and 16th Congress. The list is organized into eight categories according to the Seven Big Winner sectors and General Business Environment. It was arrived at by a group of five Philippine business groups and the seven JFC members and has been recommended to the president, the Senate president and the House speaker. As explained below, some could first be addressed in executive orders, with laws to follow. Most of these proposals are not controversial, and could, with strong executive and legislative leadership, be enacted over the next few years. Annex 4 contains a list of other potential reform laws.

Use of a presidential executive order or a department administrative order can hasten the introduction and implementation of a reform. Often within months of the executive branch decision, a new policy can be implemented by the bureaucracy. For important issues enactment of a law should eventually follow.

Congress also sometimes legislates market-unfriendly laws. These have been enacted by the president in most instances, often allowing the measure to lapse into law by not signing. Presidential vetoes are rare, as objections by the executive branch to a bill moving through the Congress are usually accommodated during the legislative process. Table 74 lists market-inimical laws enacted in recent congresses.

LEDAC

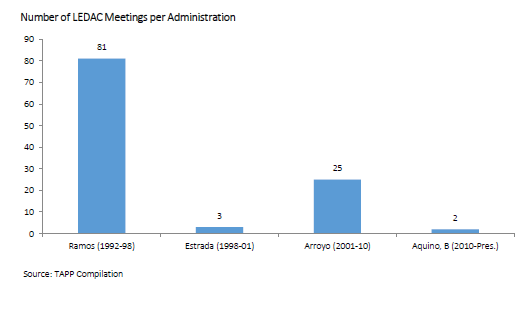

The Legislative Executive Development Advisory Council (LEDAC) was initiated during the Ramos Administration. The president and cabinet secretaries usually met with congressional leaders every two weeks both to establish legislative priorities and to discuss the status of the priority legislation in the House and Senate. During the two subsequent administrations the LEDAC met less regularly. The Executive Secretary’s office nevertheless maintained a list of LEDAC priority legislation, and the president continued to designate bills as “urgent” in order to speed their passage. However, for the last 12 years, the LEDAC has been less active than during the Ramos Administration (see Figure 191). Its revival should be considered as an effective means of advancing the legislative priorities of the new administration during the 15th Congress (2010-2013) and the 16th Congress (2013-2016).

Headline Recommendations

- The president should hold regular LEDAC meetings of executive and congressional leaders. LEDAC should prioritize the administration’s legislative agenda and monitor its progress throughout the legislative process.

- Prioritize bills that improve competitiveness, increase investment and revenue, and create jobs, in order to accelerate economic growth. Use executive orders and revision of IRRs to start reforms, following up with legislation as needed. Deter market-inimical bills.

- Pass legislation much more rapidly, especially for business and economic reforms. Prioritize key legislation that was close to final passage in the 14thCongress or that reached 2nd/3rd reading in either the House or the Senate.

Recommendations: (13)

A. The president should hold regular LEDAC meetings of executive and congressional leaders. LEDAC should prioritize the administration’s legislative agenda and monitor its progress throughout the legislative process. (Immediate action OP and Congress)

B.Prioritize bills that improve competitiveness, increase investment and revenue, and create jobs, in order to accelerate economic growth. The chairs of the committees to which such bills are referred can be asked to conduct hearings and complete their committee reports in the early months of the 15th Congress.Deter market-inimical bills. (Immediate action LEDAC and Congress)

C.Pass legislation much more rapidly, especially for business and economic reforms. Prioritize “low-hanging fruit” legislation that was close to final passage in the 14th Congress or that reached 2nd or 3rd reading in either the House or the Senate. (See Table 72) (Medium-term action Congress)

D. Set a target to pass many more investment climate reform bills in the 15th and 16th Congress. (See Table 73 for potential bills) (Medium-term action Congress)

E.Use executive orders to introduce reforms quickly. Follow-up as needed with laws to make the reforms more permanent. (Immediate action OP and executive branch departments)

F.Revising Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRRs) of laws and executive orders is another way to achieve reform. For example, removing the 60-40 equity provision of the Renewable Energy Act and completing the amendments of the BOT Act can encourage more investment in renewable energy projects and public-private partnerships. (Immediate action NEDA, DOE, DOF)

G. The Executive Secretary should assess how a bill passed by Congress affects competitiveness and job creation. The assessment should be made public. (Immediate action OP)

H.Seek to make the Foreign Investment Negative List (FINL) more positive, thereby leveling the playing field for foreign investors. Review all restrictions in the FINL to determine which continue in the national interest and recommend changes in those considered to be out of date. Implement the recommended changes. (Medium-term action OP, NEDA, DTI and other agencies, Congress, and private sector)

I.Simplify the present 45 laws regulating 46 professions to relax restrictions on foreign professionals and redefine reciprocity. Draft and seek passage of an omnibus law amending the present restrictions and establishing a uniform policy consistent with the current role of Philippine professionals in the global workplace. (Immediate action PRC and Congress)

J.Clarify that foreign investors can own firms providing services of PRC-certified professionals as long as the requirements of the Foreign Investments Act of 1991 (RA 7042) are met (US$ 100,000 paid-in capital and 50 employees). (Immediate action DTI and PRC)

K. Seek to reduce and remove discrimination against foreign firms in Philippine government procurement laws, regulations, and practices, bringing them into conformity with international best practice.234 Encourage the GRP to adhere to the WTO Agreement on Procurement. (Immediate action NEDA, DTI and Congress)

L.Encourage new investment in selected regulated public utility activities by using language similar to Section 6 of the EPIRA (RA 9136), which clearly states that power generation shall be competitive, not be considered a public utility, and not require a franchise. (Immediate action NEDA, DOJ, and relevant departments)

M.Develop a comprehensive Philippine Legal Code and Code of Regulations to create an inventory of laws and regulations. Make the inventory accessible on the internet. The Civil Code (RA 386) was signed in 1949. (Medium-term action by DOJ, Congress, and private sector)

Footnotes

- When former president Marcos lifted martial law in 1980 he restored a legislative body, which he had suspended in 1972, but made it unicameral (the Batasan Pambansa).[Top]

- R = reading; all bills must pass three readings in committee and plenary in both House and Senate before they can be sent to the president for signature.

- After the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) downgraded the RP ATO, the CAAP passed the Congress rapidly, reportedly following advocacy activity by Philippine airline companies.

- In April 2009 the Philippines was included on a small list of countries that the OECD did not consider had adequate laws requiring compliance with investigations by international tax authorities. The Secretary of Finance assured the OECD that remedial legislation would be quickly passed, met with the House and Senate leaders, introduced DOF draft bills, which completed full congressional hearings and readings and were enacted in less than one year.

- The bill allows foreign banks the same five year period as domestic banks to obtain optimal value in foreclosure proceedings involving real estate, while respecting the constitutional provision on land ownership. Other provisions of the bill requiring mandatory lending are disadvantageous to foreign banks.

- Not all proposed bills cited in the list have been fully reviewed and may not be completely supported in the cited versions of the proposed laws. “Nyd” means not yet drafted.[Top]

- When not clear from common title. Bills cited were introduced in the 14th Congress. When no bills are cited, authors are unaware of any draft legislation

- December 1999, “Report of the Preparatory Commission on Constitutional Reforms” and December 2005, “The Proposed Revision of the 1987 Constitution by the Consultative Commission, with Highlights and Primers on the Major Proposals and Background Information on the Consultative Commission.”

- Common name for “Investment and Incentives Code of the Philippines Act”

- The Government Procurement Reform Act of 2003 (RA 9184) covers procurement by all government offices and corporations. RA 9184 designates competitive bidding as the method of procurement. While goods may be obtained from either local or foreign suppliers, preference may be given to domestically-produced and manufactured goods that meet the specified standards (Article XII, Section 43). GOCCs can be awarded government contracts without going through the bidding process. The IRRs for RA 9184, revised in 2009, contain provisions regarding procurement which favor local goods and service providers.

For infrastructure projects contracted to the private sector, the BOT Law of 1990 (RA 6957) provides for the employment of Filipino labor in different phases of the construction phase (Section 2-a) which is re-affirmed in the Amended BOT Law of 1994 (RA 7718). Moreover, for infrastructure projects that require a public utility franchise, the facility operator must be at least 60% Filipino-owned (Section 2-a).

CA 138 (also known as the Flag Law of 1936), wherein the procurement of supplies, materials or public works for public use shall be purchased from domestic suppliers. In the case of public bidding, the award shall be given to the domestic entity making the lowest bid (Sections 3 & 4).[Top]